Most of the research I saw on texture dealt with

1) how the body physically senses texture, and

2) the emotional associations people have with various textures.

Regarding #1, I don’t think your readers really care about nerve endings or pressure senses or which parts of the nervous system are activated when sensing texture.

But regarding #2, it’s a big deal to mention that various textures can activate various emotions and associations in people, and thus your students can use this to their advantage if they wish to communicate a message with texture.

What Is Texture?

Texture, fabric, and weave are three of the most misunderstood words in men’s clothing.

So we’ll address them at the start of this module:)

Part of the confusion lies in the fact texture has less impact on how a garment looks. It’s more subtle than the color or the pattern of a garment – but to say it’s unimportant is to ignore the human need to touch and interact.

Texture brings in other senses beside sight – and when used properly can help a man look more approachable to a woman he’s courting or more elegant to a group he’s presenting in front of.

This may be a place to mention some theoretical “background” about texture – specifically, some notes about how and why we develop texture recognition. Feel free to use as much or as little of this information as possible.

Texture is one of the first things we notice as humans

Babies are always touching, feeling, and putting things in their mouths

- Babies are like little scientists who test the world around them

- Since they haven’t developed sight they must rely on their other senses

- Texture tells babies whether something is safe and approachable (soft toys, teddy bears) or potentially dangerous (a stone or hardwood floor, pavement)

- But there’s more to it than just danger vs. comfort.

One famous study by Dr. Harry Harlow in the ‘50s studied how baby monkeys “attach” to (form a parent-child bond with) their mothers (this is relevant, I promise).

- Read the study HERE: https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Harlow/love.htm

- A theory stated that baby monkeys will attach to wherever they get their food, no matter what the source.

- To test this theory, Harlow raised a baby monkey in a room with two “mothers”: one made with a piece of coiled wire and wood that also contained a bottle with milk. The other “mother” was soft and covered with cloth but had no milk.

- What did the baby monkeys prefer? The cloth monkey with no milk.

- Even though they got nourishment from the wire/wood “mother,” there was something about the physical contact with a softer, warmer “being” that formed a bond between mother and baby

- Harlow called this “contact comfort” and suggested that baby monkeys need it to develop properly

- “Contact comfort” may drive a lot of our texture perceptions.

- Texture and touch is one of the most primal, earliest ways that organisms learn who to cling to, and who to reject.

As adults, we still recognize that some fabrics are emotionally “warm,” “nurturing,” and give feelings of comfort, while others are can give the opposite effect.

As you will see later on, these associations are far more complex than just “warm” or “cold.”

Texture Fundamentals

So here are a few fundamental definitions and differences worth remembering:

- Texture refers to the physical surface of a piece of cloth. Sometimes it has a visible unevenness and sometimes it appears completely smooth. Texture can — but doesn’t always — affect how the color and pattern of the garment look.

- Weave is the way the threads in a piece of cloth are bound into a solid whole. The weave and the size and quality of thread used in it affect the texture of the finished cloth.

- Fabric is the actual finished cloth that gets cut up to make a garment. Confusingly, there is no standard system for how we refer to cloth. Marketers might use any combination of color, weave, raw material, thread type, or other characteristics to describe a garment — it’s entirely possible to call the same coat “gray tweed” or “wool herringbone” if it is, in fact, a jacket made from gray tweed threads in a herringbone weave.

So while fabric and weave often affect the texture of the garment, they don’t necessarily define it. You have to actually lay hands on the cloth (or at the very least see high-quality photos of it) to tell what the real physical texture is going to be like.

Why Texture Matters

The most obvious effect of texture is, of course, its comfort on your body. No one likes to wear rough, scratchy fabric. That said, most jackets made with coarse fibers are lined, and the physical effect of texture is so obvious it bears little dwelling-on:

Run your hand across anything you’re thinking of buying (or better yet try it on), and if it feels unpleasant don’t buy it. That one’s simple.

From a stylistic point of view it’s the subtler effects of texture that are interesting. The texture of your garment can influence how its color appears, how any patterns in it appear, and how formal it is.

Here it might be useful to mention the “messages” that various textures may be sending out:

- Visual “texture” gives us a mental signal that makes us think about the person wearing it in a new way

- In other words, the way a fabric looks can “prime” (or stimulate) ideas of softness, warmth, approachability, etc. even if we don’t physically touch the material.

- Consider fabrics that are considered “feminine”: silk and velvet. These fabrics suggest softness, fragility, etc.

- Leather is considered “masculine” because it’s tough, rough, and gives a mental image of a man who has been working out in the sun.

- Men and women can “soften” or “harden” their personas by adding fabric that is considered “opposite-sex”

- Women who wear leather? Men who wear silk?

- Consider a complex example:

- Denim is tough and hard at first, but can be quite comfortable when broken in

- If you want a persona that says, “I’m tough on the outside, but warm and soft once you get to know me,” denim might be able to give that off

- We have a complex mental picture of texture and just seeing a certain type of fabric can unleash a flood of associated memories, feelings, ideas, and pictures

Laboratory research has confirmed that fabric and texture can evoke emotions

- One study from 2001 gave fabric samples to fashion and textile students and had them rate them in terms of emotional/mood/cognitive factors.

- NOTE: I previously reported that this study was done at Liverpool John Moores University, but some other universities were involved as well. Just link to the study and that will be fine.

- One study from 2001 from the School of Art at Liverpool John Moores University gave fabric samples to women and had them rate them in terms of emotional/cognitive factors.

- Fleece and Tweed evoked feelings of relaxation and warmth

- Satin, Silk, and Lace evoked feelings of “faded familiarity”

- Corduroy and Leather evoked feelings of masculinity

- Lycra and Denim evoked feelings of energy

- Velvet and Irish Linen evoked feelings of “opulent poise”

Texture and Color

Picture two pieces of cloth dyed the same navy blue: one in a cotton broadcloth so smooth and tightly-woven it almost shimmers, another in thick flannel wool.

Would you expect the two cloths to look the same? Of course not. The former cloth would be good for a shirt, while the latter might make a good suit. Laid out together, the suit would appear slightly darker than the shirt, even though they were dyed with the same chemicals.

Why? Part of it has to do with the threads themselves — a thick wool thread absorbs more dye than a fine cotton one, resulting in a darker rendering of the color. But the substantial difference is actually coming from the weave itself and the way it interacts with light.

All color is light bouncing off of objects and into our eyes. When light hits a more pitted surface, less of it reflects back. The coarseness of a brushed wool thread absorbs more light than the very flat surface of a broadcloth made from smooth cotton threads.

Some garments actually derive their color from textured weaves that involve more than one color — the conventional “blue collar” shirt is usually made by weaving indigo threads one way across white threads going the other way. Slightly dimpled weaves rather than perfectly flat ones are commonly used, which results in more visual blurring of the two colors. At any kind of distance, the patchwork of blues and whites reads to a human eye as a solid blue several shades lighter than the color of the blue thread.

Texture and Pattern

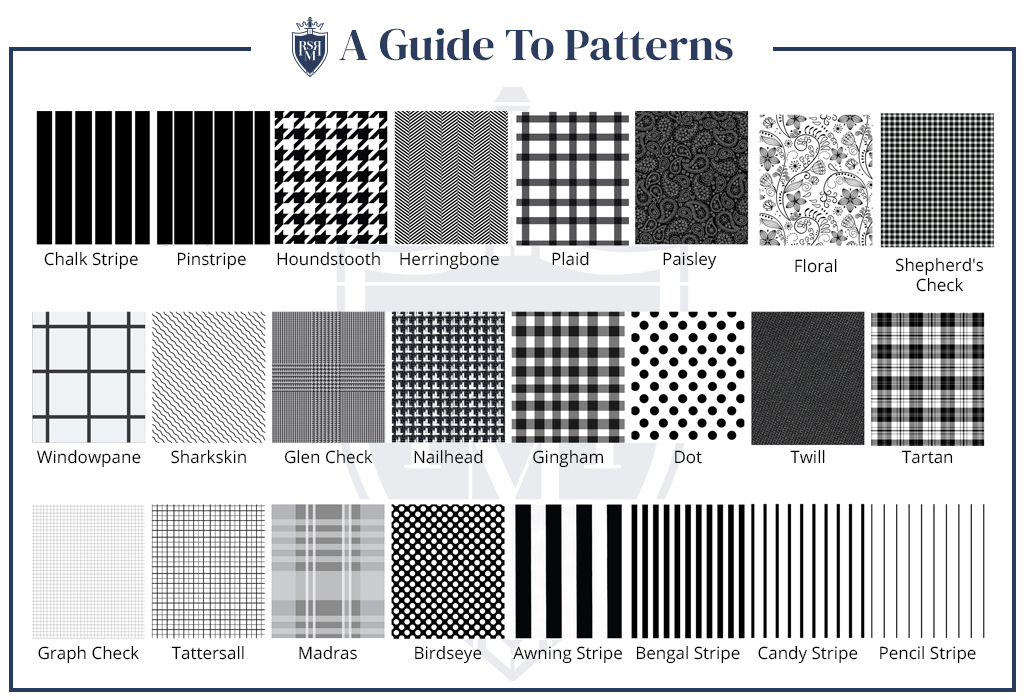

Visible textures are a form of pattern. However, not all patterns in clothing are made by textures, and not all textures produce a visible pattern.

Confused yet?

Breaking it down into the simplest possible terms, a piece of clothing can have one of four types of “pattern,” by which we mean a visible variation in coloring:

- No Pattern at All. The cloth is solid and the texture appears smooth, resulting in a completely unvaried effect. (Example — a solid blue broadcloth dress shirt.)

- Dyed Pattern, Smooth Texture. There is a visible pattern in the cloth made by either multiple colors of dye or by a solid color with stitching in a different color. Other than the stitching the cloth is smooth. (Example — a worsted wool suit in Glen plaid.)

- Solid Color, Visible Texture. The cloth is only dyed one color, but features a texture with a visible pattern. The bumps, ridges or other uneven areas of the weave create a repeating pattern. (Example — gray wool trousers with a broad herringbone weave).

- Dyed Pattern, Visible Texture. The cloth is both visibly textured and dyed multiple colors. The dyed pattern is not the same as the textured pattern and both overlap with one another. (Example — seersucker pants dyed with blue and white stripes)

The last category can be overwhelming. Apart from a few established styles (like the example of seersucker pants) it’s rare to see a piece of cloth with a visible texture and a multicolored dye pattern.

In most cases texture is used as a substitute for printed, dyed, or stitched patterns. It can be especially useful when you want a visually “busy” look but don’t want too many clashing colors.

A vertically-striped shirt doesn’t go very well with a vertically-striped suit (too much of the same general pattern), but the same shirt with a solid-colored herringbone suit looks great, and the herringbone gives you the same vertical emphasis that stripes would.

A bit of texture is also simply a way to make an otherwise solid-colored garment more unique. Pastel dress shirts are ubiquitous; pastel dress shirts in decorative weaves are less common. Adding some light texture can help a man stand out in a crowd.

Working Texture Into Your Wardrobe

A little texture goes a surprisingly long way. One or two pieces with visible texture is usually plenty in an outfit, especially when one of the pieces is a suit.

And the easiest way to do it – add a sweater!

Ok, ok I know that’s useless during the warmer months and for those of you in hotter climates.

So we’ll cover a LOT more!

Suits, Jackets, and Trousers Textures

This is where you can really make textured pieces work for you. Most suit textures are made with thick threads in visible weaves, although a few textures come from the type of thread itself (as in tweed) or from a finishing process applied to the finished cloth (as in napped flannel). A few common suit textures include:

- Worsted (Smooth but with a dull matte finish)

- Tweed (rough, hairy wool)

- Flannel (soft, fuzzy wool with a napped surface)

- Corduroy (visible vertical ridges or “wales”)

- Herringbone (visible columns of V-shapes/chevrons)

- Birdseye/Nailhead (large round dimples)

- Barleycorn (raised threads in clusters of three)

- Houndstooth (usually dyed two colors to emphasize the bumpy texture)

- Satin Weave (shimmer effect, tight weave, reserved for sons of dictators or really cheap suits:))

- Twill (very fine diagonal ribbing)

- Seersucker (deeply dimpled cotton that is woven in a ribbed fashion to create a gauze effect – air passes very easily while the fabric looks substantial)

Note that some of these can be combined — you could have a houndstooth or herringbone tweed, for example, since houndstooth and herringbone are weaves and tweed refers to the type of wool and thread used.

Shirt Textures

It’s less common to find textured dress shirts, in part because they’re often worn against the skin, where unevenness can be uncomfortable. They do exist, however, and many cloths that we think of as perfectly ordinary shirt fabrics actually have a faint texture to them:

- Broadcloth and fine oxfords (smooth surface)

- Coarse oxford (very fine, close-spaced dimples)

- Poplin (deeper dimples made by two different sizes of threads)

- Herringbone (vertical columns of V-shapes/chevrons)

- Twill (fine diagonal ribbing)

- Gauze or Lawn (cotton woven in a manner to allow maximum airflow while not being transparent)

Business shirts tend to be broadcloth or tightly-woven oxfords, though some poplins are also woven so tightly that the dimpling almost vanishes, making them business-appropriate as well. For a more daring look, a herringbone shirt can work with a suit, so long as the herringbone weave is very fine and the threads are all one color rather than two contrasting colors.

Textured Accents

We don’t normally think of our ties and shoes as having texture of their own, but they all do. Many are, of course, perfectly smooth, but that doesn’t mean you don’t have other options:

- Knit ties (bumpy surface)

- Brogued shoes (decorated with punched holes)

- Suede shoes (not just for elvis and pretty easy to take care of)

- Woven shoes and belt (made of interlaced leather strips)

- Leather jackets (from smooth to distressed)

- Tooled belts (solid leather with stamped designs)

- Silk pocket squares (shimmery-smooth texture)

Be weary of mixing too much texture. Textured accents with larger textured pieces such as a tweed suit and a knit tie, for example, makes you look downright wooly. Reserve this look for liberal arts professors:)

From time to time, however, the textures can complement nicely, as in the case of a dimpled seersucker suit with a woven leather belt. You may need some trial and error in from of a mirror to figure out what works and what doesn’t if you’re working with multiple textured pieces in a single outfit.

Texture Made Easy

- Using textures in your wardrobe is an easy skill to acquire once you are aware of it. Just remember the fundamental points:

- Stick to one or two textured pieces at maximum. You can break this rule, but you should have a specific reason for doing it.

- Textured fabric with colored patterns make the “busiest” clothing. Pair them with simple pieces or you’ll get too overwhelming.

- Light texture adds interest and uniqueness to a dark solid, making them ideal for business wear that needs to stand out without breaking dress standards.

- Textured accents can spice up an outfit that’s otherwise smooth and simple.

- Tall men and skinny men can wear more texture than short men and broad men. The lanky men benefit from a little extra “weight,” while the stout men want a sleek look with no distracting bumps and shapes on the way up.

A wardrobe that’s completely free of texture is a dull wardrobe. As long as you stick to these basic guidelines, there’s really no limit to the textures and weaves you can play with. Your style will be better for it.